When your doctor suspects liver damage, you might worry about a needle going into your liver. But today, that’s not always necessary. Two main tools - FibroScan and serum scores - are changing how we check for liver scarring without surgery. They’re faster, safer, and increasingly used in clinics across the UK and beyond. But which one works better? And why do some patients get conflicting results? Let’s cut through the noise.

What FibroScan Actually Measures

FibroScan is a handheld device that sends gentle vibrations through your skin and into your liver. These vibrations travel at different speeds depending on how stiff your liver is. Stiffness equals scarring - or fibrosis. The result? A number in kilopascals (kPa). Normal is between 2 and 7 kPa. Above 12 kPa usually means advanced scarring. Above 14 kPa? That’s often cirrhosis.

The machine uses two probes: one for average-sized people (S probe), and a larger one (XL probe) for those with higher body fat. If you have a BMI over 28, your provider should use the XL probe. Otherwise, the test might fail. One patient in Birmingham told me their first two attempts didn’t work because the wrong probe was used. The third try - with the XL probe - gave a clear result.

FibroScan also measures fat in the liver through something called CAP (Controlled Attenuation Parameter). A CAP score above 260 dB/m means you have moderate fat buildup. Above 290? That’s severe fatty liver. This is huge for people with NAFLD - non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - which affects about 1 in 4 adults globally.

But FibroScan isn’t perfect. It can give false highs if you’ve eaten recently, have an active liver infection, or have heart failure. The test needs at least 10 good readings, and the results must be consistent. If the interquartile range is over 30% of the median, the result is unreliable. In real-world clinics, about 1 in 10 tests are inconclusive. That’s why some patients end up having the test repeated - or worse, sent for a biopsy anyway.

Serum Scores: Blood Tests That Predict Scarring

While FibroScan is physical, serum scores are all in your blood. They use simple lab values - AST, ALT, platelets, age - and plug them into formulas. The most common ones are FIB-4, APRI, and ELF.

FIB-4 is the cheapest and easiest. It costs about $10 to calculate. If your score is below 1.3, you’re very unlikely to have advanced scarring. If it’s above 2.67, you’re at high risk. In primary care, FIB-4 is often built into electronic records. One GP in Birmingham told me her clinic’s screening rate jumped from 12% to 67% after FIB-4 became automatic.

APRI is older but still used. A score above 2.0 suggests cirrhosis. But it’s less accurate for early scarring. That’s where ELF comes in. It measures three proteins linked to liver repair. It’s more expensive than FIB-4 - around $50 - but more precise for detecting moderate to severe fibrosis.

Here’s the catch: serum scores are better at ruling out disease than confirming it. A low FIB-4 score means you probably don’t need a FibroScan. But a high score? It doesn’t tell you how bad it is. That’s why doctors don’t use them alone.

Why FibroScan and Serum Scores Don’t Always Agree

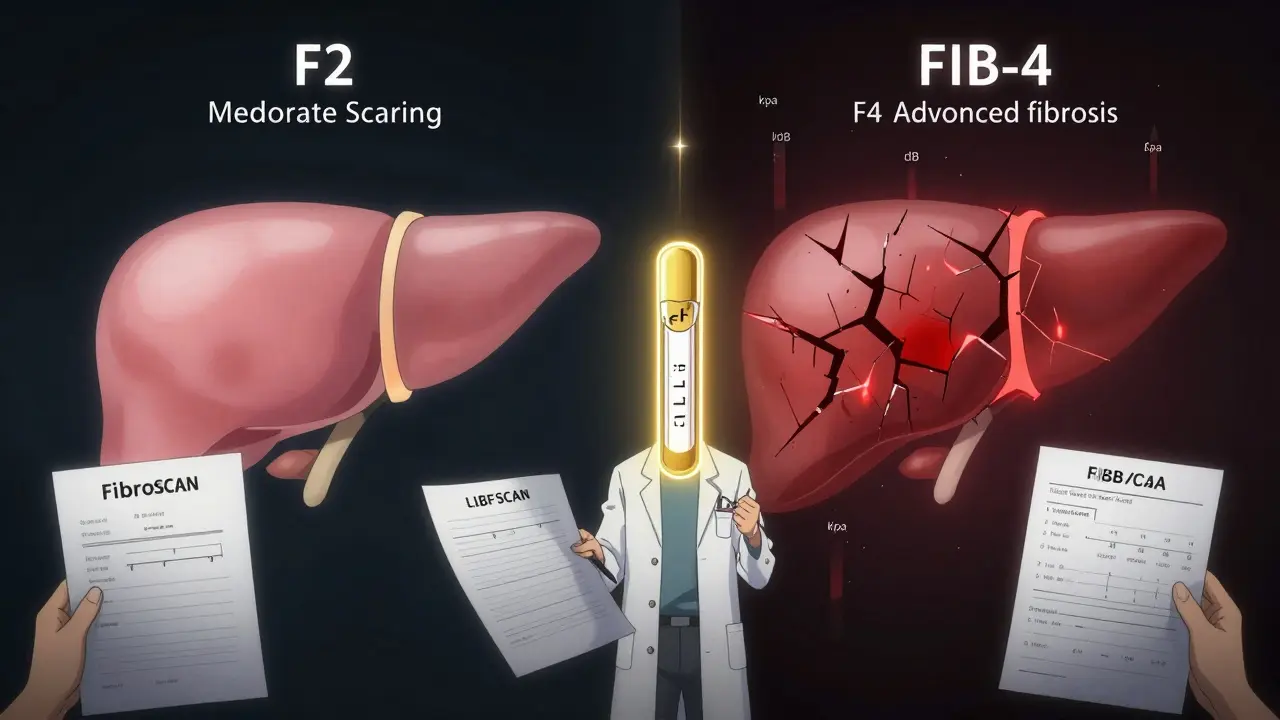

Imagine this: Your FIB-4 says you’re at high risk for advanced fibrosis. Your FibroScan says you’re only at F2 - moderate scarring. You’re confused. Which one’s right?

A 2023 study found FibroScan missed nearly half of the patients with advanced scarring (F3/F4). FIB-4 missed even more - only 16.8% of those patients were flagged correctly. But here’s the twist: FibroScan was 99% accurate for cirrhosis. FIB-4 was 90% good at ruling out advanced fibrosis.

So the real story isn’t which test is better. It’s how they’re used together. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends a step-by-step approach:

- Start with FIB-4. If it’s low (<1.3), you’re safe. No more tests needed.

- If it’s high (>2.67), go straight to FibroScan.

- If FIB-4 is in the middle (1.3-2.67), use FibroScan to clarify.

- If results conflict, or if you have diabetes or obesity, add ELF or consider biopsy.

This method cuts biopsy needs by 70%. That’s huge. Biopsies carry small risks - bleeding, pain, even death in rare cases. Avoiding them isn’t just easier. It’s safer.

Where These Tests Fall Short

FibroScan struggles with obesity. Not because the machine can’t work - but because fat blocks the vibrations. The XL probe helps, but it’s not magic. One patient with a BMI of 38 had three failed attempts before the XL probe worked. The cost jumped from £80 to £280.

Serum scores have their own blind spots. FIB-4 is less accurate under age 35. That’s a problem because NAFLD is rising fast in younger adults. Also, if you have an active hepatitis infection or recent alcohol use, your AST and ALT levels spike. That can make FIB-4 look worse than it is.

And then there’s CAP. It overpredicts fat in obese people. A patient with mild fat on biopsy might get a CAP score of 300 - making them think they have severe fatty liver. In reality, the score is inflated by body fat, not liver fat.

Even the best tests can’t replace clinical judgment. A 2022 commentary in the American Journal of Gastroenterology said it plainly: “No single non-invasive test should replace the doctor’s experience.”

What’s New in 2025?

The field is moving fast. Echosens released FibroScan 730 in April 2024. It uses AI to flag unreliable results before the test even ends. Early trials show it cuts technical failures by 22%.

There’s also FIB-5 - a new serum score that adds blood sugar to the mix. It’s especially useful for people with type 2 diabetes, who are at higher risk for rapid liver damage. In a 2024 study, FIB-5 correctly identified advanced fibrosis in 89% of diabetic NAFLD patients.

Meanwhile, MRI-based elastography (MRE) is getting more attention. It’s more accurate than FibroScan - 95% for detecting moderate fibrosis - but costs 10 times more. Most clinics won’t use it unless FibroScan and serum scores are inconclusive.

And yes, smartphone apps are being tested. But they’re still experimental. Don’t trust an app on your phone to tell you if your liver is scarred.

What Should You Do?

If you’re at risk - overweight, diabetic, have high cholesterol, or drink alcohol - ask your GP for a FIB-4 test. It’s free or cheap. If it’s low, relax. You’re likely fine.

If it’s high, ask for a FibroScan. Don’t panic if your score is in the middle. Many people are. That’s why we use both tests.

If you’re confused by conflicting results - like one test says F2 and another says F4 - ask about the ELF test. It’s not always available, but it’s the best tiebreaker.

And if you’re told you need a biopsy? Ask why. Has FibroScan been done? Was FIB-4 checked? Was ELF considered? Too often, biopsies are ordered because no one thought to use the non-invasive tools first.

Liver scarring doesn’t happen overnight. It’s slow. And it’s often reversible - if caught early. That’s why these tests matter. Not because they’re perfect. But because they’re better than a needle.

Key Takeaways

- FibroScan gives immediate, visual liver stiffness and fat readings - but fails in up to 15% of cases, especially in obesity.

- FIB-4 is a cheap, blood-based score that’s excellent at ruling out advanced fibrosis - but poor at confirming it.

- APRI is outdated for most cases; ELF is more accurate but costlier and less widely available.

- Never rely on one test alone. Use FIB-4 first, then FibroScan for intermediate or high-risk results.

- Combined use of FibroScan + FIB-4 + ELF can avoid 80% of unnecessary biopsies.

Can FibroScan detect early liver damage?

Yes - FibroScan can detect early scarring (F1-F2) with good accuracy, especially when using the right probe and proper technique. But it’s most reliable for advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) and cirrhosis. For early stages, serum scores like FIB-4 are better for screening, while FibroScan helps confirm progression.

Is FibroScan better than a liver biopsy?

For most people, yes. Biopsy is invasive, carries small risks, and can miss scarring due to sampling error. FibroScan is painless, quick, and gives a full-liver picture. But biopsy is still needed when results conflict, or if cancer or other rare diseases are suspected. Think of FibroScan as the first step - biopsy as the last.

How often should I get tested?

If you have NAFLD or other risk factors and your first test is normal, repeat every 2-3 years. If you have moderate fibrosis (F2), repeat annually. If you’re on treatment - like weight loss or diabetes control - your doctor may test every 6-12 months to track improvement. Don’t test more often unless there’s a reason.

Can I do a FibroScan at home?

No. FibroScan requires a trained operator, proper calibration, and controlled conditions. Smartphone apps or DIY devices aren’t validated and shouldn’t be trusted. Always get tested in a clinic, hospital, or specialist center with experience in liver diagnostics.

What if my FibroScan result is borderline?

Borderline results (e.g., 7-10 kPa) are common. They mean your liver is somewhere between normal and scarred. Don’t panic. Combine it with FIB-4. If FIB-4 is low, you’re likely fine. If FIB-4 is high, add the ELF test. If all three are unclear, your doctor may suggest a follow-up in 6 months - or a biopsy if you have other risk factors like diabetes or high ALT.

Next Steps

If you’re at risk for liver disease, start with your GP. Ask for a FIB-4 calculation - it’s part of routine blood work. If you’re overweight or diabetic, ask if you’ve been screened for fatty liver. Most people haven’t.

If you’ve had a FibroScan and don’t understand your result, ask for a copy. Know your kPa and CAP numbers. Write them down. Bring them to your next appointment.

And if you’re told you need a biopsy - ask if you’ve tried the non-invasive route first. Too many people skip the easier steps. You don’t have to. The tools are here. Use them.

8 Responses

FibroScan changed everything for me. I had NAFLD and was terrified of a biopsy. My first test failed because they used the wrong probe, but when they switched to XL, it was clear - F2, not F4. No needles, no recovery time. Just a quick scan and a number. I wish more GPs knew how to interpret it properly.

I’m a primary care doc in Ohio, and we started using FIB-4 automatically last year. Our screening rate went from 12% to 67%. Patients don’t even notice it’s happening - it’s just part of their annual bloodwork. And the best part? We’ve cut down on unnecessary referrals by half. Simple tools, huge impact.

It’s fascinating how medicine is shifting from invasive certainty to probabilistic wisdom. We used to demand a biopsy because we feared missing something. Now we accept that a combination of imperfect tools - FIB-4, FibroScan, ELF - gives us a clearer, safer picture than any single needle ever could. The liver doesn’t scream; it whispers. And we’re finally learning to listen.

There’s poetry in that. Not in the machines, but in the humility they demand of us. We don’t need to know everything to help. We just need to know enough - and to know when to stop.

And yet, we still cling to the myth of the definitive test. The biopsy as holy grail. But the truth is, the liver heals. Slowly. If we give it space. And these tools? They give us that space.

I’ve watched patients breathe easier after a low FIB-4. No more sleepless nights. No more imagining cirrhosis in every ache. That’s not just medicine. That’s peace.

And yes, CAP overestimates fat in obesity. Yes, FIB-4 fails in young adults. But we don’t need perfect. We need better. And we’re getting there.

One day, we’ll look back and wonder why we ever stuck needles into people for a number that a blood test and a vibration could give us safely.

Until then, let’s keep pushing for access. For training. For the XL probe in every clinic. For FIB-4 in every EHR. For ELF where it matters.

Because liver disease doesn’t care about your income or your insurance. It just waits. And these tools? They’re the quiet rebellion against neglect.

Let me be unequivocal: The integration of non-invasive diagnostics into routine hepatology practice represents a paradigmatic leap forward in preventive medicine. The confluence of FibroScan’s elastometric precision and FIB-4’s cost-efficiency constitutes a synergistic triage architecture that obviates the archaic, risk-laden biopsy paradigm. One must acknowledge the statistical supremacy of EASL’s algorithmic cascade - wherein FIB-4 functions as the gatekeeper, FibroScan as the clarifier, and ELF as the arbiter of ambiguity. The reduction in biopsy utilization by 70–80% is not merely a logistical triumph; it is a moral imperative fulfilled.

Moreover, the advent of FibroScan 730’s AI-driven quality assurance mechanisms and FIB-5’s incorporation of glycemic metrics signifies a quantum leap in predictive analytics. One cannot overstate the clinical utility of these innovations for the burgeoning cohort of metabolic syndrome patients. The future is not merely non-invasive - it is intelligent, adaptive, and patient-centric.

Let us not be luddites. Let us not fetishize the scalpel. The data is irrefutable: the needle is obsolete.

Anyone who trusts a vibrating machine over a real biopsy is either naive or willfully ignorant. These so-called 'non-invasive' tests are guesswork dressed up as science. I’ve seen patients get false negatives - and then die of cirrhosis because they were told they were 'fine.' The U.S. is obsessed with avoiding discomfort - even when it costs lives. Biopsy is still the gold standard. Period. End of story. No 'maybe,' no 'but,' no 'step-by-step.' Just facts. And facts don't care about your feelings.

One thing that’s rarely discussed: the training gap. A FibroScan isn’t a gadget - it’s a skill. I’ve seen technicians use the S probe on patients with BMI 35 and then shrug when the result is unreliable. The same goes for interpreting FIB-4 in young diabetics. We’re deploying powerful tools without equipping the people who use them. Until clinics invest in certification and ongoing education, these tests will keep failing - not because they’re flawed, but because we’re careless.

And yes, FIB-5 is promising. But it’s not magic. It still needs validation in diverse populations. Don’t rush adoption. Do it right.

Western medicine is losing its way. Why rely on machines and blood math when the old way - the real way - was always better? In my country, we still respect the doctor’s hand, the needle, the truth. These soft tests are for people who fear pain. Weakness is not progress.

How quaint. A ‘stepwise approach’? How very 2020. The real issue isn’t the tests - it’s the institutional inertia. Most NHS clinics still don’t have FibroScan machines. And ELF? Only available in three London hospitals. Meanwhile, patients are being sent for biopsies because the system refuses to upgrade. This isn’t innovation - it’s bureaucratic negligence dressed up as clinical wisdom.