How the First Generic Wins - and Why the Rest Still Come

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic company to file a challenge gets a 180-day window to sell without competition. During that time, they charge 70-90% of the original price and capture 70-80% of the market. That’s not luck - it’s the law. The Hatch-Waxman Act is a 1984 U.S. law that balances patent rights with generic competition by giving the first generic company a financial reward for challenging weak or invalid patents. This reward covers the $5-10 million it often costs to fight patent lawsuits in court. For many generic manufacturers, this period is the only chance to recoup their investment.

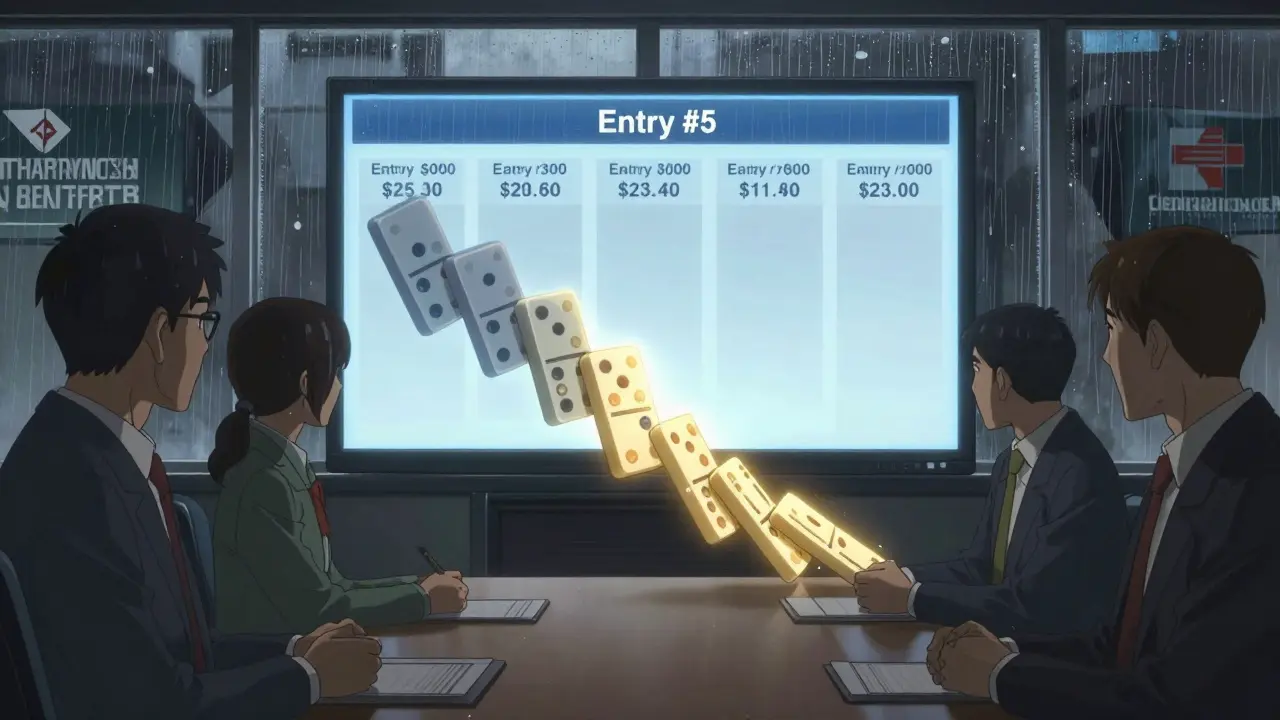

But here’s the twist: after those 180 days, the floodgates open. Competitors who waited in the wings jump in - and prices collapse. In the Crestor (rosuvastatin) market, prices dropped from $320 a month for the brand to just $10 within 18 months after eight generic makers entered. That’s not an outlier. The FDA found that with five or more generic competitors, prices stabilize at only 17% of the brand’s original cost. The steepest drop? Between the second and third entrants. That’s when the market shifts from premium pricing to pure cost warfare.

The Second Wave: Who Shows Up and How

It’s not just any company that enters after the first. The second and third generics aren’t random players. They’re usually well-funded firms with experience in complex manufacturing or partnerships with contract manufacturers. Why? Because the first generic already did the hard work: they proved the drug is bioequivalent, cleared regulatory hurdles, and sometimes even won patent lawsuits. Subsequent entrants can piggyback on that data, cutting development costs by 30-40%. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

Many of these later entrants are authorized generics - same drug, same factory, same formula, but sold under a different label. These are often launched by the original brand company itself, through a subsidiary. In the Januvia (sitagliptin) market, Merck launched its own authorized generic the exact day the first generic hit shelves. Within six months, it captured 32% of the market. That’s not competition - it’s a preemptive strike. It slashes the first generic’s revenue by 30-40% and turns what should’ve been a golden 180 days into a race to the bottom.

Other competitors rely on contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs). About 78% of second-and-later entrants use CMOs to avoid spending millions on their own production lines. That’s why you see so many generic shortages after multiple entries - when one CMO has a quality issue, it can knock out three or four brands at once. The FDA reported that 62% of generic shortages involve products with three or more manufacturers, all sharing the same supply chain.

It’s Not Just About Price - It’s About Access

Getting FDA approval is only half the battle. The real fight happens in the back offices of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and group purchasing organizations (GPOs). These middlemen control which drugs end up on insurance formularies - and they don’t care who got approved first. They care about who offers the lowest price.

Most PBMs now use "winner-take-all" contracts. That means if you’re the cheapest, you get 100% of the business. Even if you’re the fifth generic to enter, if you undercut the others by 5%, you take the entire market. That’s why some companies enter late and still win - they’re not trying to compete on speed. They’re competing on price.

But here’s the catch: it takes 9-12 months for a new generic to get formulary placement. During that time, they’re stuck with 5-10% market share, even though they’re approved by the FDA. Meanwhile, the first generic has already locked in contracts, built relationships, and secured distribution. That’s why some experts call it a "second first-mover advantage." The first to sign the deal wins - not the first to file.

Patent Games and Legal Delays

Brand companies aren’t just sitting back. They’re fighting back - legally. Between 2018 and 2022, they filed over 1,200 citizen petitions targeting drugs that already had one generic approved. Each petition delays the next generic by an average of 8.3 months. These aren’t legitimate safety concerns. They’re legal stalling tactics. One petition can cost a new entrant millions in lost revenue.

And then there are patent settlements. In 2022 alone, there were 147 agreements between brand and generic companies where the brand paid the generic to delay entry. The Humira biosimilar market is a perfect example: six companies agreed to staggered entry dates between 2023 and 2025. No one gets in early. No one gets to crash the party. Prices stay higher longer. These deals are legal - for now - but they’re under increasing scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission.

Why Some Markets Never Fill Up

Not all drugs attract five or six generics. Some stay with just two or three - and prices stay stubbornly high. Why? Complexity. Drugs that require special handling - like oncology meds or injectables - are harder and more expensive to make. That keeps out smaller players. In cancer generics, prices hover at 35-40% of the brand price even with multiple competitors. Compare that to cardiovascular drugs, where five manufacturers drive prices down to 12-15%.

There’s also consolidation. In 2018, there were 142 companies holding generic drug approvals. By 2022, that number dropped to 97. Many small manufacturers couldn’t survive the price wars. They either shut down or got bought out. The result? Fewer competitors. Slower price erosion. And markets that don’t behave the way they’re supposed to.

The Future: More Competition, But Not Necessarily Better Outcomes

By 2027, experts predict 70% of simple generic markets will have five or more competitors, with prices at 10-15% of the brand. But that doesn’t mean patients will have better access. With so many players chasing pennies, quality control suffers. Shortages become common. Manufacturers exit. Prices bounce back up.

Meanwhile, complex generics and biosimilars - which cost $100-250 million to develop - will likely stay with just two or three competitors. Prices for these will hover around 30-40% of the brand. And authorized generics? They’ll be on 40-50% of top-selling drugs by 2027, up from 25% today. That means brand companies will keep a foot in the generic market, protecting their profits even after patents expire.

The system was designed to lower prices and increase access. But instead, it’s created a high-stakes game of timing, legal maneuvering, and financial risk. The first generic wins big. The rest fight for scraps. And patients? They get cheaper drugs - but sometimes, they don’t get them at all.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Markets?

There’s growing pressure to fix this. Some experts, like former FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb, suggest long-term contracts to stabilize prices and prevent manufacturers from fleeing the market. Others, like Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, argue we need to limit how many companies can enter simple generics - not to protect profits, but to prevent shortages and ensure quality.

One thing’s clear: the current model is unsustainable. Too many players chasing too little profit. Too many supply chains with too few backups. Too many legal delays blocking real competition. The next phase of generic drug entry won’t be about who files first - it’ll be about who can deliver reliably, consistently, and affordably. And that’s not just a business challenge. It’s a public health one.

9 Responses

The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to balance innovation and access. But now it’s just a legal loophole for profit maximization. First-mover advantage? More like first-mover monopoly. And the authorized generics? That’s not competition-that’s corporate sabotage disguised as market dynamics.

It’s not about price anymore. It’s about control.

This entire system is a grotesque farce orchestrated by pharmaceutical oligarchs. The FDA, PBMs, and even Congress are complicit. The 180-day window? A carefully engineered illusion to maintain price stability while giving the illusion of competition. The real winners? The lawyers and the hedge funds that own the CMOs.

first generic gets rich. everyone else gets crumbs. and the patients? they get shortages. classic capitalism. lol

You know... when you really sit with this-when you let the weight of it settle into your bones-you realize this isn’t just about drugs. It’s about the death of trust. The system was built on the idea that competition would lower prices, but instead, it’s built on the idea that profit must be extracted at every level-even from the sick. And isn’t that the tragedy? We’ve turned healing into a derivatives market. The first generic doesn’t win because they’re better-they win because they’re the first to gamble. And the rest? They’re just the house’s collateral.

And yet, we still call this ‘free market.’ What a cruel joke.

I just read this while waiting for my prescription to be filled. And honestly? I’m exhausted. I’m not mad-I’m just… tired. We’ve been sold this idea that generics = cheap = good. But what if ‘cheap’ means ‘unreliable’? What if ‘competition’ means ‘no one can stay in business’? I just want my meds to be there when I need them. That’s not too much to ask, right?

The PBM winner-take-all model is a textbook example of negative-sum game dynamics. It incentivizes race-to-the-bottom pricing while externalizing operational risk onto CMOs and supply chains. The result? Structural fragility. And the FDA’s reactive oversight? Pure regulatory capture. We’re not fixing the market-we’re just rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

So the brand companies just slap their own generic on the shelf the day the first one drops? That’s not a market-it’s a rigged casino. And the worst part? We all know it. But we still pay. Because what choice do we have? 😑

This is why we need public manufacturing. No more CMOs. No more PBMs. No more patent games. Just make the drugs, sell them cheap, and move on. We can do this. We just need the will. We’re not broke-we’re just being robbed.

The real villain here isn’t the first generic-it’s the system that rewards litigation over innovation. Why fight patents when you can just wait and undercut? Why build capacity when you can rent it? We’ve turned medicine into a game of financial chess-and the patients are the pawns. And don’t even get me started on how the FDA’s backlog is basically a delay tactic for Big Pharma. 🤷♂️