When a company files a patent in the United States, it’s easy to assume the protection lasts 20 years - and that’s true in the U.S. But if that same patent is filed in China, Germany, Brazil, or Japan, the expiration date might be different. Not because the law is broken, but because the world doesn’t have one single patent clock. Even though nearly every country agrees on a 20-year term from the filing date, the real expiration date is shaped by delays, fees, extensions, and local rules that can add years or cut them short - sometimes by accident.

Why the 20-Year Rule Isn’t Always What It Seems

The global baseline for patent protection is 20 years from the earliest filing date. This standard came from the TRIPS Agreement in 1995, which forced countries like the U.S. to change their old 17-year-from-grant system. But the moment you start digging into individual cases, you find that this 20-year clock doesn’t run the same everywhere.In the U.S., if your patent application takes three years to get approved because the patent office was slow, you might get extra time added - called a Patent Term Adjustment (PTA). In 2022, the average U.S. patent received 558 extra days of protection just because of delays. That’s almost a year and a half added to your 20-year term. Meanwhile, in India, no such adjustment exists. If the patent office takes five years to examine your application, you don’t get any extra time. Your patent still expires exactly 20 years from the day you filed.

Japan is another example. If the examination process takes more than three years, you can apply for an extension. China now does the same after its 2021 patent law update. But in Brazil, even though the law says 20 years, the backlog is so bad that many patents only get 12 to 15 years of real protection. The clock runs, but the patent doesn’t actually get granted until years later.

What Happens After You File? The PCT Maze

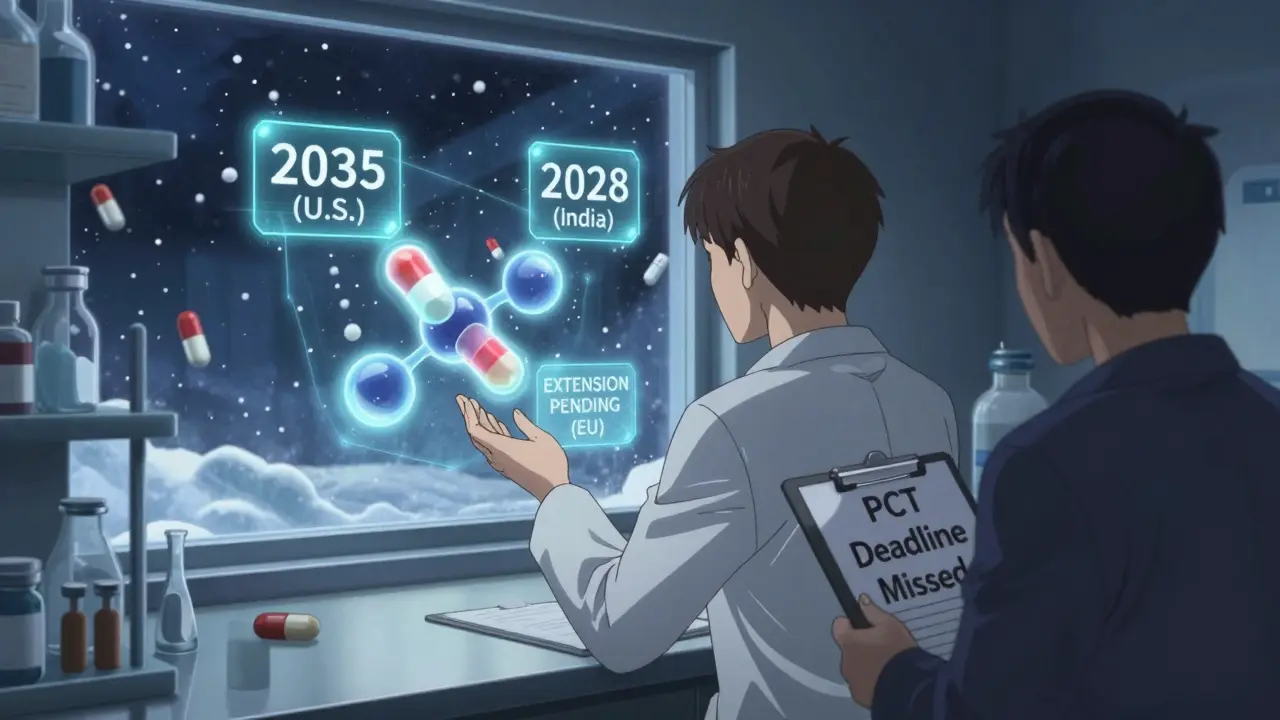

Most companies don’t file patents in just one country. They use the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which lets them file one application that covers over 150 countries. But here’s the catch: the PCT doesn’t give you a global patent. It just delays the hard part.After filing a PCT application, you have 30 or 31 months to decide which countries you want to enter. The U.S. gives you 30 months. Canada, China, and most of Europe give you 31. If you miss that deadline, you lose rights in that country - even if your original filing was years ago. That means your patent might expire in Germany on January 1, 2030, but in Brazil, it never even got started because you missed the window.

And even within those windows, some countries allow extensions. Japan lets you file late with a 2-month grace period if you explain why. The U.S. lets you file late with a fee. But if you don’t act, your patent rights vanish - no second chances.

Pharmaceutical Patents: The Exception That Breaks the Rule

If you’re protecting a new drug, the 20-year clock doesn’t tell the whole story. It takes 8 to 12 years just to get a drug approved by regulators. That leaves only 8 to 12 years to make money before generics hit the market.To fix this, many countries offer Patent Term Extensions (PTE). The U.S. allows up to 5 extra years, plus a 6-month bonus if the drug was tested in children. The European Union offers the same through Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). In Japan and China, extensions are possible too - but only if regulatory delays were unreasonable.

But not all countries play along. Australia gives extensions for office delays, but not for regulatory ones. India gives none at all. And in countries like Mexico or South Korea, the rules are so unclear that companies often have to hire legal teams just to guess what the expiration date will be.

Maintenance Fees: The Silent Killer of Patents

Even if you nail the timing and get your patent granted, you’re not done. Most countries require you to pay maintenance fees - usually every few years - to keep the patent alive.In the U.S., you pay at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years. Miss one, and your patent dies. There’s a 6-month grace period, but you pay extra. In Europe, fees are due annually. In Switzerland, you pay only once - at grant. In Mexico, you pay four times: at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years.

Here’s the scary part: many small companies and startups let these fees lapse because they don’t track them. A patent might be valid for 18 years - but if the 7.5-year fee is missed, it’s dead. No one notices until a competitor starts selling the same product. That’s how valuable technology gets stolen - not by copying, but by neglect.

Utility Models: The Short-Lived Alternative

Not every invention needs 20 years. In Germany, China, Japan, and over 40 other countries, you can file a utility model - a simpler, faster, cheaper version of a patent. These usually last only 6 to 10 years. They’re perfect for products with short life cycles: gadgets, packaging, tools, or mechanical parts.But here’s the trade-off: utility models can’t protect chemical formulas, software, or complex processes. They’re also not available in the U.S., Canada, or the U.K. So if you’re protecting a medical device, you might file a utility model in Germany for quick protection, and a full patent in the U.S. for longer coverage. You’re managing two different clocks on the same invention.

The New EU Unitary Patent: One System, One Clock

In June 2023, the European Union launched the Unitary Patent - a single patent that covers 17 EU countries with one filing, one fee, and one expiration date. It’s the closest thing the world has to a true international patent.But even this system follows the same 20-year rule from filing. It doesn’t change the timeline - it just simplifies it. You still need to pay maintenance fees. You still need to watch for extensions. And you still can’t use it in non-EU countries like Switzerland or Norway.

What This Means for Global Businesses

If you’re a multinational company - especially in pharma, tech, or manufacturing - you’re not managing one patent. You’re managing dozens, sometimes hundreds, of patents with different expiration dates. Pfizer tracks over 500 patent expirations across 80 countries. Johnson & Johnson has teams dedicated to mapping out which patents expire where, and when generics can legally enter the market.For startups, it’s even harder. Many assume that filing a U.S. patent protects them globally. It doesn’t. A patent filed in California expires in 2040 - but if you never filed in India, someone there can copy your product tomorrow. And if you missed the PCT deadline in Brazil, you’ve lost rights there forever.

There’s no software that automatically calculates every patent’s expiration date across every country. Too many variables: delays, fees, extensions, national laws, and changing regulations. That’s why companies hire patent attorneys - not just to file, but to track, predict, and plan.

What’s Next? The Fight Over Fairness

Developing countries argue that long patent terms block access to medicines and technology. Developed nations say strong patents drive innovation. WIPO and the WTO are still negotiating how to balance these interests.Indonesia and Vietnam recently extended their patent terms from 15 to 20 years to match global standards. But countries like India and South Africa still resist patent extensions for drugs. The result? A patchwork system where a cancer drug might be protected in the U.S. until 2035, but in India, it’s off-patent in 2028.

For now, the only way to stay ahead is to know the rules - not just in your home country, but in every market you care about. Because in global patent law, time isn’t just a measure. It’s money. And if you’re not tracking it, someone else is.

12 Responses

Let me tell you something - this whole patent system is a scam cooked up by Big Pharma and Silicon Valley to keep the little guy down. You think 20 years is long? Try living in India where your grandma’s diabetes medicine gets ripped off because some corporate lawyer in Delaware got a 5-year extension while we wait 8 years just to get our application reviewed. It’s not about innovation - it’s about control. And don’t even get me started on maintenance fees. They’re not fees - they’re execution warrants for startups. If you can’t afford to pay every 3.5 years, your invention dies. That’s not capitalism. That’s feudalism with a patent attorney.

So let me get this straight - the U.S. gives extra time for bureaucratic delays, but other countries just say ‘tough luck’? That’s not fairness - that’s weakness. We built the most efficient patent office on Earth, and now we’re being punished because other nations can’t keep up? The TRIPS Agreement was a mistake. We should’ve just said, ‘If you can’t handle 20 years, don’t bother.’ We don’t need to bend over backwards for countries that can’t even process applications without a 5-year backlog. This isn’t global cooperation - it’s global appeasement.

One must consider the epistemological underpinnings of intellectual property in a post-colonial global order. The 20-year paradigm, ostensibly neutral, is in fact a hegemonic construct - a neocolonial mechanism by which Western capital imposes temporal sovereignty over innovation in the Global South. India’s refusal to extend pharmaceutical patents is not ‘backwardness’ - it is epistemic resistance. The PCT, far from being a neutral instrument, functions as a legal Trojan horse, allowing multinational entities to entrench monopolies under the guise of procedural efficiency. Maintenance fees? A regressive tax on the Global Innovation Poor. The Unitary Patent? Merely the EU’s attempt to rebrand colonial extraction as regulatory harmony.

I just... I really appreciate how this breaks it all down 😭 I had no idea how much variation there was - like, I thought patents were just ‘20 years’ everywhere. The part about Brazil only getting 12-15 years of actual protection? That’s heartbreaking. And the maintenance fees - oh my gosh, I bet so many small inventors lose their patents without even realizing it. Someone should make a free tracker for this. Please? 🙏 I’d donate. I’d volunteer. I’d cry happy tears.

Okay so I’m a small business owner and I just filed a patent last year - I thought I was done after the USPTO approval. But now I’m panicking because I didn’t even know about PCT deadlines. I’m like 2 months away from missing my window for Europe. Can someone tell me if there’s a cheap way to check all this? I’m not a lawyer. I just make cool phone stands. I don’t want to get owned by some Chinese company because I missed a deadline. 😅

Hey, I just wanted to say thanks for writing this. It’s clear, detailed, and doesn’t talk down to people. A lot of patent stuff is written like it’s for lawyers only. You made it human. Also - utility models? That’s a game-changer for hardware startups. I’ve been thinking about filing one in Germany for my new tool design. Didn’t even know it existed until now. You just saved me months of confusion.

People still think this is about ‘fairness’? Wake up. This isn’t a moral issue - it’s a war. The U.S. invests billions into R&D. India and Brazil sit on their hands for years, then rip off our drugs the second the clock ticks. And you call that ‘access to medicine’? No. You call it theft dressed up as justice. The fact that we give extensions for regulatory delays is a kindness. They should be grateful. Instead, they scream ‘colonialism’ while stealing our tech. Pathetic.

They say patents are for innovation. But I’ve seen it - companies file 50 patents just to block competitors. One patent for the shape of the button. One for the color of the packaging. One for the sound it makes when you press it. That’s not innovation. That’s legal harassment. And the PCT? Just a fancy way to delay the inevitable - which is that someone in Shenzhen is already reverse-engineering your ‘groundbreaking’ widget while you’re paying your 7.5-year fee. This whole system is rigged.

Ohhhhh, so that’s why my cousin’s startup in Bangalore got crushed? He filed in the U.S., thought he was covered, then got sued by a guy in Mumbai selling the exact same thing. He didn’t even know India doesn’t recognize PCT delays as extensions. And the maintenance fees? He skipped the third payment because he thought ‘it’s just paperwork.’ Now he’s broke and angry. This isn’t just technical - it’s emotional. Imagine pouring your soul into something, then losing it because you didn’t know a form had a deadline in Geneva. We need better education. Not more laws. More empathy.

I work in public health. I’ve seen kids in rural Kenya waiting for cancer drugs that cost $10,000 a month because the patent hasn’t expired. Meanwhile, the same drug costs $50 in India because the patent expired there 7 years ago. This isn’t about ‘protecting innovation’ - it’s about choosing who lives and who dies. The 20-year rule feels like a luxury we can’t afford anymore. Maybe we need a new model - one where life-saving tech has a shorter clock. Not because we hate patents. But because we love people.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the current international patent regime, while imperfect, remains the most robust framework for incentivizing technological advancement across heterogeneous jurisdictions. The disparities in examination timelines and maintenance obligations are not indicative of systemic failure, but rather reflect the divergent administrative capacities and economic priorities of sovereign states. Harmonization, while desirable, must be pursued incrementally, with due regard for national sovereignty and developmental context. To impose uniformity without regard for institutional readiness would engender greater inefficiency, not less.

Wait - so if you miss a maintenance fee in Europe, your patent dies - but in the U.S., you have a 6-month grace period? That’s insane. Why is one country more ‘forgiving’ than another? And why does no one talk about this? This isn’t just legal - it’s psychological. Inventors are left in this fog of uncertainty. You spend years building something, then you’re told: ‘Pay $1,200 in June or lose everything.’ No warning. No reminder. Just silence. And then - boom - someone else sells your invention. And you’re the villain for not paying a fee you didn’t even know you had to pay. This system is broken. And no one wants to fix it because the lawyers are making too much money.