Most people assume their insurance covers generic drugs cheaply-after all, generics are supposed to be the affordable version of brand-name meds. But here’s the truth: bulk buying and tendering is what actually makes those low prices possible. Without it, many generics would cost 10 times more. Insurers don’t just pick the cheapest option off the shelf. They run competitive bidding wars, lock in volume deals, and swap out expensive generics for cheaper ones with the same active ingredients. It’s not magic. It’s procurement-and it’s saving billions every year.

How Generic Drugs Got So Cheap (And Why It’s Not Always Fair)

The modern generic drug system started in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, generic makers had to prove their drugs worked from scratch. After the law, they only needed to show they were the same as the brand-name version. That cut approval time and cost. Suddenly, dozens of companies could make the same pill for a fraction of the price. By 2023, 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were generics. But here’s the catch: just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s cheap. Some generics still cost $50, $100, even $200 a month. Why? Because the system isn’t designed to pass savings to patients. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-the middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drug makers-control the pricing. They create formularies, set copays, and negotiate rebates. And sometimes, they profit more when the generic is more expensive.Bulk Buying: The Power of Buying in Massive Quantities

Insurers don’t buy one prescription at a time. They buy millions. When a company like OptumRx or CVS Caremark negotiates with a generic manufacturer, they don’t ask for 100 bottles. They ask for 10 million. That kind of volume gives them leverage. Manufacturers will drop their price just to keep the order. It’s simple economics: lower margin per unit, higher total profit from volume. Take lacosamide, a generic seizure drug. When the first generic hit the market in 2022, it saved $1.2 billion in its first year alone. That’s not because the drug became magically cheaper. It’s because five new companies started making it. The competition forced prices down by 85% within months. That’s bulk buying in action: more suppliers = lower prices.Tendering: The Silent Auction That Controls Your Copay

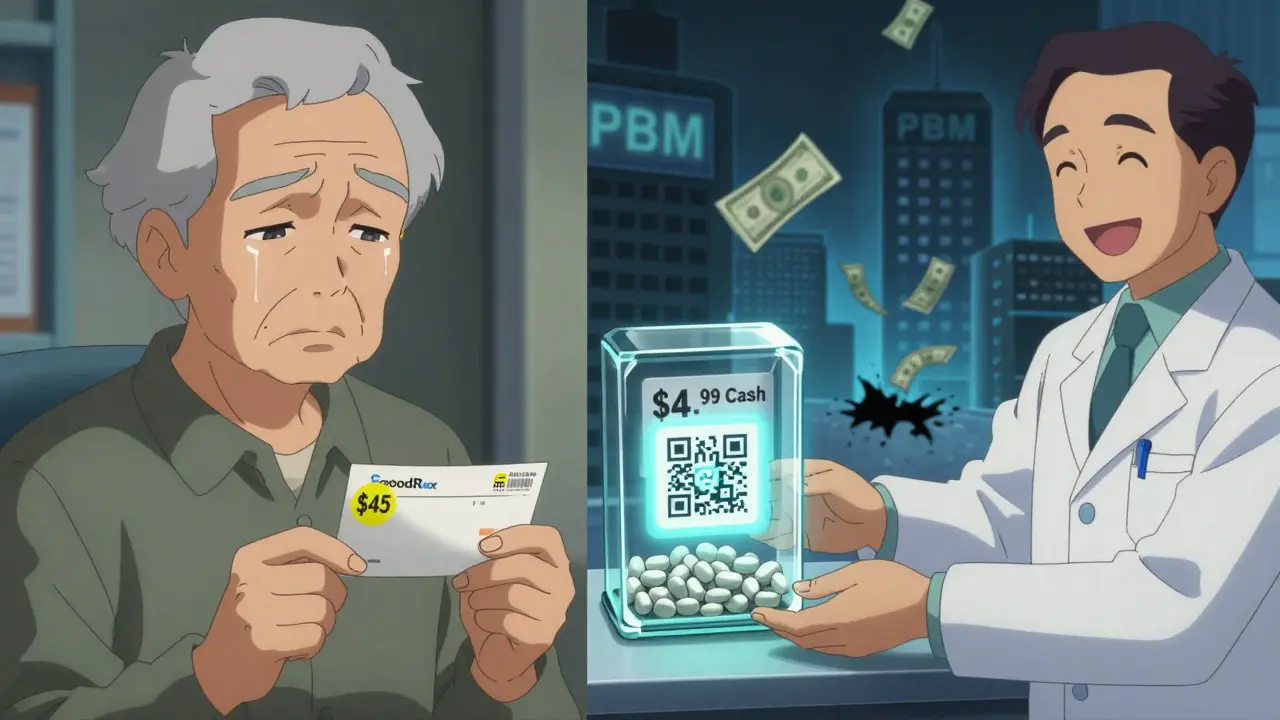

Tendering is where insurers turn bulk buying into a competitive auction. They identify a high-cost generic-say, a blood pressure pill that costs $45 per prescription. Then they send out a request for bids. Three manufacturers respond. One offers $8. Another says $6. A third says $4. The insurer picks the lowest. But here’s the twist: the patient’s copay might still be $15. Why? Because the PBM keeps the difference between what the insurer pays and what the pharmacy charges. That’s called “spread pricing.” In 2022, a JAMA Network Open study found that PBMs often hid these spreads from insurers. So even when a drug’s true cost dropped to $4, the plan sponsor didn’t know. The patient still paid $15. The insurer paid $12. The PBM pocketed $8. That’s not a typo. The PBM made more money on a $4 drug than the manufacturer did.

Transparency Is Changing the Game

Some people are bypassing the system entirely. Companies like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company and GoodRx let you pay cash-no insurance needed. A 2023 NIH study found these direct-to-consumer pharmacies offered median savings of 76% on expensive generics. One Reddit user paid $87 through insurance for a generic statin. Paid $4.99 cash at Cost Plus. Same pill. Same pharmacy chain. Just no middleman. Blueberry Pharmacy, a newer player, charges exactly $15/month for blood pressure meds. No surprise bills. No formulary changes. No rebates hidden in fine print. Users love it. One review said, “I finally know what I’m paying. No more guessing.”Why Your Insurance Still Charges You Too Much

Despite all this, most insurers still use traditional PBM models. Why? Because they’re easy. PBMs handle the paperwork, manage pharmacy networks, and promise savings. But the savings aren’t always real. In fact, 78% of Medicare Part D plans still put generics on higher copay tiers-even though they cost less than $10 to make. That means you’re paying $25 for a pill that costs $3. The insurer doesn’t even get the full discount. The PBM keeps it. The FDA says first generics create the biggest savings. But once a second or third maker enters, prices crash. That’s when insurers should switch. But many don’t. They stick with the same supplier because switching requires work. And work costs money.What Happens When Prices Drop Too Low

There’s a dark side to aggressive tendering. When insurers demand prices so low that manufacturers can’t profit, they stop making the drug. That’s what happened with albuterol inhalers in 2020. The price dropped below $1 per inhaler. No one could make money. Production stopped. Hospitals ran out. Eighty-seven percent of surveyed hospitals reported shortages. It’s a vicious cycle. Too much pressure = no supply. Too little pressure = inflated prices. The trick is finding the sweet spot where manufacturers still make money, and patients still pay less.

How Insurers Actually Save Money (And How You Can Too)

Smart insurers don’t just pick the lowest bid. They do three things:- They track which generics are costing the most-then swap them out for cheaper equivalents.

- They require manufacturers to meet minimum volume commitments in exchange for contract terms.

- They demand transparency. California’s SB 17 law forces PBMs to reveal spreads over 5%. More states are following.

The Bigger Picture: $445 Billion Saved-But Who’s Really Benefiting?

In 2023, generics and biosimilars saved the U.S. healthcare system $445 billion. That’s more than the entire budget of the Department of Education. But here’s the uncomfortable truth: most of that money didn’t go to patients. It went to insurers, PBMs, and pharmacies. The average patient still skips doses because they can’t afford their meds. A 2022 KFF survey found 41% of Medicare beneficiaries cut pills in half to make them last. The system works-if you’re a PBM. It works-if you’re a large insurer with leverage. It doesn’t work well if you’re a 62-year-old on a fixed income trying to afford three generics a month.What’s Next? More Transparency, More Choice

In January 2024, Medicare finally required PBMs to disclose pricing details. That’s a start. Companies like Navitus Health Solutions are already reporting 22% lower generic costs for employers by cutting out traditional PBM layers. More employers are asking: Why pay a middleman if we can buy direct? The future of generic drug pricing won’t be controlled by PBMs. It’ll be controlled by consumers who refuse to overpay-and by insurers who finally demand real savings, not hidden rebates.If you’re paying more than $10 for a common generic, you’re likely being overcharged. Ask your insurer: “What’s the true cost of this drug? Who’s getting the rebate?” If they can’t answer, it’s time to shop elsewhere.

How do insurers save money on generic drugs?

Insurers save by buying generics in massive volumes and running competitive bidding processes called tendering. They negotiate lower prices by committing to buy millions of doses, then switch to cheaper alternatives when new manufacturers enter the market. This drives prices down by 80-90% in some cases.

Why do I still pay a lot for generics even though they’re supposed to be cheap?

Because pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often use “spread pricing”-they charge your insurer one price, pay the pharmacy another, and keep the difference. Your copay might be $20, but the drug only cost $5. The PBM pockets the rest. Many insurers don’t even know this is happening.

Can I save money on generics without using my insurance?

Yes. Cash prices at pharmacies like Cost Plus Drug Company, GoodRx partners, or even Costco are often lower than insurance copays. A 2023 NIH study found cash prices saved patients 76% on expensive generics and 75% on common ones. For example, metformin costs $4 cash vs. $15-$45 with insurance.

What’s the difference between bulk buying and tendering?

Bulk buying means purchasing large volumes to get lower prices. Tendering is the process of inviting multiple manufacturers to bid for a contract. Together, they work: insurers buy in bulk, then use tendering to pick the lowest bidder, forcing competition and driving prices down further.

Why do generic drug shortages happen?

When insurers and PBMs demand prices so low that manufacturers can’t make a profit, they stop producing the drug. This happened with albuterol inhalers in 2020-prices dropped below production cost, and 87% of hospitals ran out. It’s a side effect of extreme cost-cutting.

Are all generics the same?

They have the same active ingredient and are FDA-approved as equivalent. But not all generics are made by the same company, and some are more expensive due to brand loyalty, limited competition, or PBM incentives. Insurers need to check which specific generic is driving costs-not just assume all are cheap.

15 Responses

The systemic exploitation of generic drug pricing through PBM spread pricing is not merely a market inefficiency-it is a structural betrayal of patient trust. When manufacturers are forced to compete on margins so thin that production becomes untenable, the resulting shortages are not accidental; they are predictable outcomes of misaligned incentives. The FDA’s approval framework, while brilliant for accelerating access, has been weaponized by intermediaries who extract value without adding utility. Transparency laws like SB 17 are the bare minimum. What we need is a public utility model for essential generics-where pricing is decoupled from profit-seeking middlemen entirely.

You people are delusional if you think this system is broken. Insurance exists to pool risk, not to be your personal discount broker. If you can’t afford $15 for metformin, maybe you shouldn’t be taking it. People who complain about cash prices being lower are just lazy-they don’t want to shop around. My uncle takes six generics and pays $12 a month with insurance. He’s fine. Stop whining.

My grandmother in Delhi takes her blood pressure pills every day, and she pays ₹12 for a month’s supply at the local pharmacy-no insurance, no middleman. She doesn’t know what a PBM is, but she knows her body. When I told her about the $45 copay in the U.S., she just laughed and said, ‘In India, we call that robbery.’ The truth? The system isn’t broken-it was never designed for people like her. We’ve turned medicine into a financial instrument. And now we’re surprised when people die because they can’t afford the paperwork.

The PBM ecosystem operates under a principal-agent problem of epic proportions. The insurer (principal) delegates pricing authority to the PBM (agent), who internalizes externalities via spread pricing and rebate capture-creating a perverse incentive structure wherein cost containment is suboptimal for the agent but maximized for profit. The result is a Pareto-inefficient allocation of pharmaceutical expenditure. The solution? Vertical integration of pharmacy networks under fiduciary governance models with mandatory disclosure thresholds, as codified in California SB 17. Without structural re-engineering, this remains a classic case of regulatory capture.

For anyone reading this and thinking ‘I’ll just use GoodRx’-you’re right. But it’s not that simple. Not everyone has a smartphone, reliable internet, or knows how to navigate pharmacy networks. My mom is 71. She still uses paper scripts. She doesn’t know what a PBM is. She just shows up at the counter and pays what they tell her. The real tragedy isn’t the $80 difference between cash and insurance-it’s that the system doesn’t care if you understand it. It just wants your copay.

Let’s be real-this whole thing is a circus. Insurers play the long game, PBMs play the shell game, and patients? We’re the clowns holding the tickets. I once paid $37 for a generic antibiotic through insurance. Paid $3.99 cash at Walmart. Same pill. Same day. Same pharmacist. He looked at me and said, ‘You’re not the first.’ I asked him why he didn’t tell people. He shrugged: ‘They don’t ask. And if they did, I’d lose my job.’ That’s the real story. It’s not about greed. It’s about silence.

Is it not the height of existential irony that we have commodified the very thing that sustains life? We treat pharmaceuticals like widgets in a supply chain while ignoring the ontological weight of a human body in need. The tendering process, while economically rational, is ethically bankrupt. We optimize for cost, not care. We reward efficiency, not empathy. And in doing so, we have created a system where the most vulnerable are priced out of survival-not by market forces, but by moral failure.

lol so insurance is fake? i knew it. i paid 40 bucks for a 30 day supply of omeprazole. went to cost plus and got it for 5. same bottle. same label. same damn thing. my pharmacy tech said ‘everyone does this now’ and winked. why do we even have insurance if cash is always cheaper? someone explain this to me like im 5

My cousin in Mumbai takes his diabetes medicine for 20 rupees a month. He doesn’t have insurance. He doesn’t need it. He just walks to the pharmacy and pays. In India, we don’t have PBMs. We don’t need them. We just buy medicine like we buy rice. Why can’t America be like that?

I just checked my last prescription. Insurance copay: $28. Cash price: $4.75. I’m not mad. I’m just… disappointed. Like, I used to think insurance was helping me. Turns out it was just charging me extra to be confused.

Oh wow, so the system is rigged? Shocking. Next you’ll tell me the IRS is also taking a cut. Look, if you’re paying more than $10 for a generic, you’re either not trying or you’re trusting a system that was designed to profit off your ignorance. My dad used to say: ‘If someone’s making money off your pain, they’re not your friend.’ Time to stop being a sucker.

We’re not just talking about drugs here. We’re talking about the soul of healthcare. When you turn medicine into a spreadsheet, you stop seeing people. You see line items. You see margins. You see rebates. And when you do that, you lose the point entirely. The goal isn’t to save $445 billion. The goal is to keep people alive. And right now, the system is choosing profit over life-and we’re all complicit because we’re too tired to fight it.

Let me get this straight-Americans are mad because they’re paying $15 for a pill when they could pay $5? That’s your crisis? Meanwhile, China is building hospitals in Africa and we’re crying about metformin? Get a grip. This is what happens when you let entitlement culture replace personal responsibility. If you can’t afford your meds, get a second job. Or move to India. Problem solved.

so like… if i pay cash and save money… am i being unethical? like… is it wrong to not use insurance if it’s a scam? i feel guilty but also… so much money saved. i just dont know what to think anymore. help??

There’s a deeper issue here that the article barely touches: the commodification of medical necessity. Generics are not commodities-they are lifelines. The tendering model assumes perfect information, perfect competition, and rational actors. But in reality, patients are not price-sensitive shoppers. They are sick people. Their choices are constrained by fear, ignorance, and lack of access to alternatives. When insurers optimize for cost without considering these human variables, they create systemic harm under the guise of efficiency. The solution isn’t just more transparency-it’s a fundamental rethinking of healthcare as a public good, not a market transaction. We need to decouple pharmaceutical access from profit motives entirely. Until then, we’re not fixing a broken system-we’re just polishing the chains.