Every time you fill a prescription for a generic drug, you’re caught in the middle of a hidden negotiation that has nothing to do with your doctor, your pharmacy, or even your insurance plan. The real players? Pharmacy Benefit Managers-PBMs-and they control how much you pay, whether you know it or not.

Who Really Sets the Price of Your Generic Pills?

You might think your insurance company decides how much a generic drug costs. But that’s not how it works. PBMs-like OptumRx, CVS Caremark, and Express Scripts-are the middlemen who actually set the price. They negotiate with drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and insurers behind closed doors. These three companies control about 80% of the U.S. PBM market, meaning they hold nearly all the power when it comes to pricing generics.

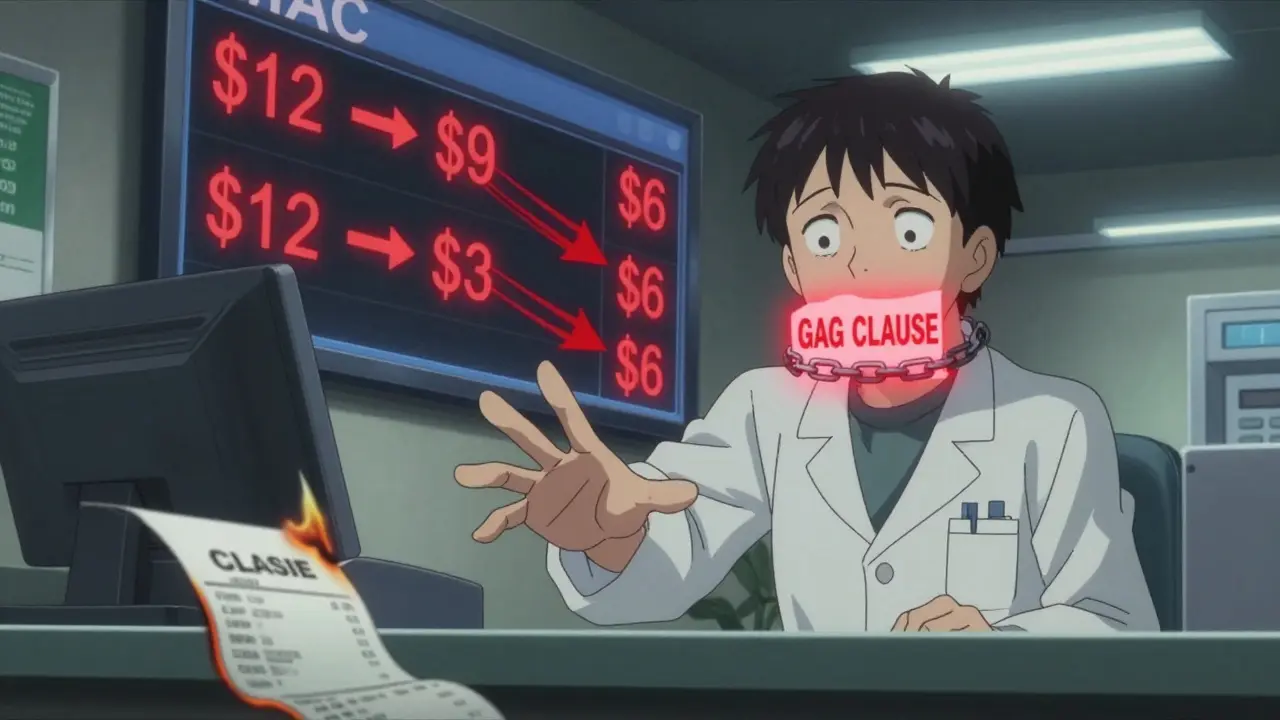

Here’s the catch: the price you see on your receipt isn’t the price the pharmacy gets paid. PBMs create a list called the Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC), which is the most they’ll reimburse a pharmacy for a generic drug. But here’s where it gets messy: that MAC price is often lower than what the pharmacy actually paid to buy the drug. And if the pharmacy doesn’t make up the difference, they lose money.

How Spread Pricing Tricks You Into Paying More

One of the biggest hidden practices is called spread pricing. It works like this: your insurer agrees to pay the PBM $45 for your generic blood pressure pill. The PBM then tells your pharmacy they’ll be reimbursed $12 for it. The $33 difference? That’s the PBM’s profit. You never see it. You’re told your copay is $15 because that’s what your plan says. But if you walked into the pharmacy and paid cash, you might’ve paid $4.

This isn’t rare. A 2024 Consumer Reports survey found that 42% of insured Americans have paid more out-of-pocket for a generic drug than the cash price. One Reddit user posted: “I paid $45 for my generic metformin through insurance. Cash was $4. I called my pharmacy and they said they were forced to charge me that because of my PBM contract.”

And it’s worse for people on fixed incomes. Many seniors on Medicare Part D are hit with surprise bills because their plan’s formulary changes without warning. A drug they’ve been taking for years suddenly gets moved to a higher tier-or gets dropped entirely-and their copay jumps from $5 to $50 overnight.

Why Your Pharmacy Can’t Tell You the Truth

Pharmacists often know the cash price is lower. But most PBM contracts include gag clauses-legal clauses that forbid pharmacists from telling you about cheaper options. In 2024, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported that 92% of PBM contracts still contain these gag clauses. That means your pharmacist can’t say: “Hey, if you pay cash, you’ll save $40.”

Even when pharmacists try to help, they’re stuck. They have to use different software systems for each PBM, each with its own rules, reimbursement formulas, and payment delays. Many independent pharmacies spend 200-300 hours a year just trying to decode PBM contracts. And if a PBM changes its MAC list without notice-which happens in 41% of cases-pharmacies get stuck with losses.

The Hidden Costs Behind the Numbers

Behind every generic drug price is a web of rebates, discounts, and clawbacks. Drug manufacturers give PBMs huge rebates-sometimes up to 80% off the list price-if the PBM puts their drug on a preferred list. But here’s the twist: those rebates don’t go to you. They go to the insurer or the PBM. And because your copay is often based on the drug’s list price (not the discounted price), you end up paying more.

Dr. Joseph Dieleman from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation put it bluntly: “Higher list prices mean bigger rebates. Bigger rebates mean more profit for PBMs. And more profit for PBMs means higher out-of-pocket costs for patients.”

Independent pharmacies are paying the price. Between 2018 and 2023, over 11,300 independent pharmacies closed because they couldn’t survive the low reimbursement rates. Many now rely on “clawbacks”-where PBMs take money back after paying the pharmacy-just to break even. One pharmacist in Ohio told a local news outlet: “I filled a $12 generic last week. Got paid $10. Two days later, the PBM clawed back $3. I lost $5 on a pill that cost me $8 to buy.”

What’s Changing-and What’s Not

There’s pressure building. In September 2024, the Biden administration issued an executive order banning spread pricing in federal programs, starting January 2026. Forty-two states are now passing laws to force PBMs to disclose their pricing practices. The Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2025 would require PBMs to pass 100% of rebates to insurers-and ideally, to you.

But the system is still rigged. Even as regulators crack down, drug manufacturers are raising list prices to compensate. The pharmaceutical industry argues these rebates fund innovation. But the numbers tell a different story: PBMs made $15.2 billion in 2024 from spread pricing alone, and 68% of that came from generic drugs.

The real question isn’t whether the system is broken. It’s whether it was ever designed to serve patients.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to accept this. Here’s what actually works:

- Always ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?” Even if you have insurance, cash prices for generics are often lower.

- Use apps like GoodRx or SingleCare. They show real-time cash prices from nearby pharmacies.

- Check if your pharmacy offers a discount program. Many independent pharmacies have their own low-cost generic lists.

- Call your insurer and ask: “Is my drug on the MAC list? What’s the maximum they’ll reimburse?”

- If you’re overcharged, file a complaint with your state’s insurance commissioner. Many states now track PBM abuses.

Some employers are starting to cut out PBMs entirely. A small business in Alabama switched to a direct contracting model with a pharmacy network-and cut generic drug costs by 60% in six months. It’s possible. It just takes knowing how the game is played.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Generics make up 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. But they only account for 23% of total drug spending. That’s because the system isn’t about saving money-it’s about moving money around. PBMs, insurers, and manufacturers all benefit. Patients? They’re the ones left holding the bill.

And it’s not just about pills. It’s about trust. If you can’t trust your pharmacy to tell you the truth, or your insurer to show you the real price, then the whole system is broken.

The next time you pick up a generic, don’t just pay. Ask. Compare. Push back. You’re not just a patient-you’re the customer. And you deserve to know what you’re really paying for.

Why is my generic drug more expensive with insurance than without?

This happens because of spread pricing. Your insurance plan pays the PBM a higher price than what the PBM reimburses your pharmacy. The difference becomes profit for the PBM. Meanwhile, your copay is often based on the drug’s list price, not the discounted rate. Cash prices, especially for generics, are often much lower because they don’t include these hidden administrative fees.

What is a MAC list and how does it affect me?

MAC stands for Maximum Allowable Cost. It’s the highest amount your PBM will pay a pharmacy for a generic drug. If the pharmacy paid more than the MAC to buy the drug, they lose money on your prescription. Sometimes, the MAC is set so low that even the cash price is cheaper. This is why your copay might be $15 when the drug costs $4 cash.

Can my pharmacist tell me the cash price?

Legally, many cannot-because most PBM contracts include gag clauses that forbid them from telling you about lower cash prices. However, since 2020, federal law has banned gag clauses in Medicare Part D, and many states have followed suit. If your pharmacist refuses, ask to speak to the manager or file a complaint with your state’s insurance department.

Are there alternatives to using my insurance for generics?

Yes. Many pharmacies offer cash discount programs for common generics-like metformin, lisinopril, or levothyroxine-for under $10. Apps like GoodRx, SingleCare, and RxSaver let you compare prices across pharmacies in real time. Some independent pharmacies have their own low-cost lists. Paying cash can save you 70-90% compared to using insurance with high copays.

Why do generic drug prices vary so much between pharmacies?

Because each pharmacy has different contracts with different PBMs. A drug might cost $4 at one pharmacy because they’re paid $12 by their PBM and bought it for $8. At another, the PBM only reimburses $6, so they charge you $15 to cover their loss. There’s no national standard-just a patchwork of private deals that change weekly.

Is the PBM system going to change soon?

Yes, but slowly. Starting January 2026, spread pricing will be banned in federal programs like Medicare and Medicaid. At least 42 states are passing transparency laws requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing. The 2025 Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act could force PBMs to pass all rebates to insurers. But manufacturers may raise list prices to compensate, so the full impact remains uncertain.

10 Responses

okay but like… why are we still surprised? 😒 i paid $38 for metformin last month. cash was $3. my pharmacist looked at me like i was crazy for asking. guess i’m the weird one for thinking drugs should be affordable.

this is why i use GoodRx religiously 🙏 i used to just let insurance handle everything until i found out i was paying 10x more. now i check every script. sometimes it’s $2. sometimes it’s $12. but i never just accept the copay anymore. you’re not broken if you’re mad about this - the system is.

so let me get this straight - the people who are supposed to be helping us get cheaper meds are the ones making bank off us paying more? 🤡 genius. absolute genius. and the worst part? they’ve got laws on their side. it’s not a glitch. it’s the business model.

oh my god. i just realized my grandma’s $5 copay for lisinopril went to $52 last month and no one told her why. she cried because she thought she was being punished for getting older. turns out, some PBM just changed the MAC list and her pharmacy got clawed back $7. she’s on fixed income. she can’t afford to be a lab rat for corporate greed. this isn’t healthcare - it’s a pyramid scheme with pill bottles.

this is all a setup. PBMs are just the tip. Big Pharma owns them. The FDA is in their pocket. Your doctor? Paid to push the right scripts. Even GoodRx? They take a cut too. You think you’re fighting the system? Nah. You’re just a pawn in a 12-layered corporate onion. And the only way out? Cash. Always cash. Never insurance. Ever.

It is not merely a matter of financial exploitation - it is a systemic violation of the social contract between the medical-industrial complex and the American citizen. The MAC list, by its very design, is a mechanism of economic coercion, wherein the pharmacy - a small business often operating on razor-thin margins - is compelled to absorb losses that are, in turn, masked by gag clauses that violate the fundamental right to informed consent. One cannot be said to have made a rational healthcare decision if the cost of the drug is deliberately obfuscated. The rebates, clawbacks, and spread pricing are not merely unethical - they are, in the most literal sense, fraudulent. And yet, the Department of Health and Human Services continues to permit this charade under the guise of ‘market efficiency.’ It is a moral abdication of the highest order.

I’ve spent years studying healthcare economics, and what strikes me most is how this system inverts the idea of value. We’re told generics are cheaper - but they’re only cheaper if you don’t use insurance. That’s not efficiency. That’s a distortion. The real tragedy isn’t the money lost - it’s the trust eroded. When your pharmacist can’t tell you the truth, when your insurer hides the math, when your government allows it - we stop being patients and become data points. Maybe the answer isn’t better regulation. Maybe it’s refusing to play the game at all. Cash. Always cash. And if you can, help someone else learn how.

My aunt in rural Ohio just told me her pharmacy closed last month. Said the PBM changed the MAC on her meds three times in six months. She’s 72. Walks two miles to the next town for her prescriptions now. I don’t know how to fix this. But I know we can’t keep pretending it’s normal.

usa problem. other countries dont have this. pbms are american cancer

you people are so weak. if you can’t afford your meds, stop being lazy and get a job. or move to canada. we’re not paying for your $4 pills while you sit on your couch complaining about PBMs. this is capitalism. you think medicine should be free? go live in a socialist dystopia. i pay my taxes and still get charged $15 for my blood pressure med - so what? suck it up. the system works for the people who work.