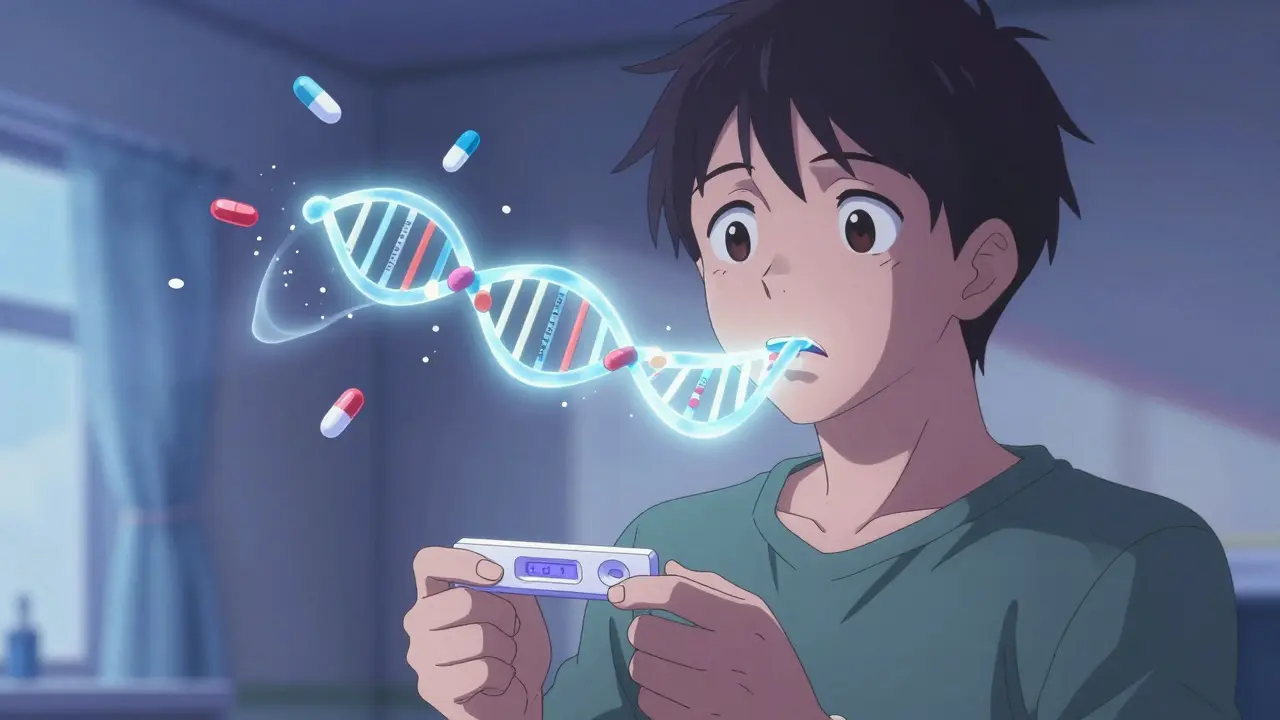

What if you could avoid a dangerous drug reaction before it even happens? For some people, genetic testing for drug metabolism isn’t science fiction-it’s the difference between feeling better and ending up in the hospital. You’ve probably heard of DNA tests for ancestry or health risks, but pharmacogenetic testing is different. It doesn’t tell you if you’ll get cancer or have blue eyes. It tells you how your body will handle the pills you’re prescribed.

How Your Genes Control Your Medications

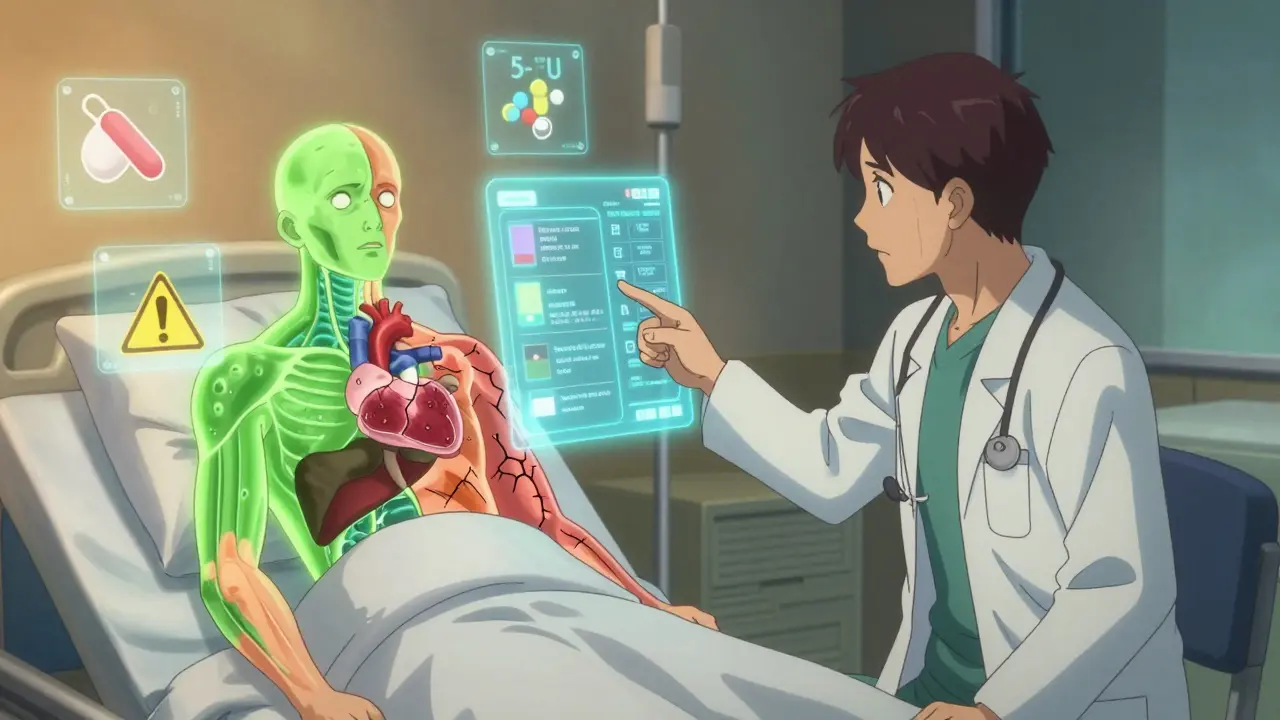

Your body doesn’t process every drug the same way. Two people can take the same pill at the same dose and have completely different outcomes. One feels relief. The other gets sick. That’s not random. It’s often because of genes. The key players are enzymes in your liver, especially those from the CYP450 family. The most important ones for medication response are CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and DPYD. These enzymes act like molecular scissors-they break down drugs so your body can get rid of them. But not everyone has the same scissors. Some people have scissors that cut too slowly. Others have scissors that cut too fast. And some don’t have scissors at all. If you’re a slow metabolizer of CYP2D6, common antidepressants like fluoxetine or codeine can build up in your blood and cause dizziness, nausea, or even breathing problems. If you’re a fast metabolizer, those same drugs might not work at all. The same goes for clopidogrel (Plavix), a blood thinner. About 30% of people have a CYP2C19 variant that stops the drug from working, putting them at higher risk for heart attacks or strokes.When Testing Makes a Real Difference

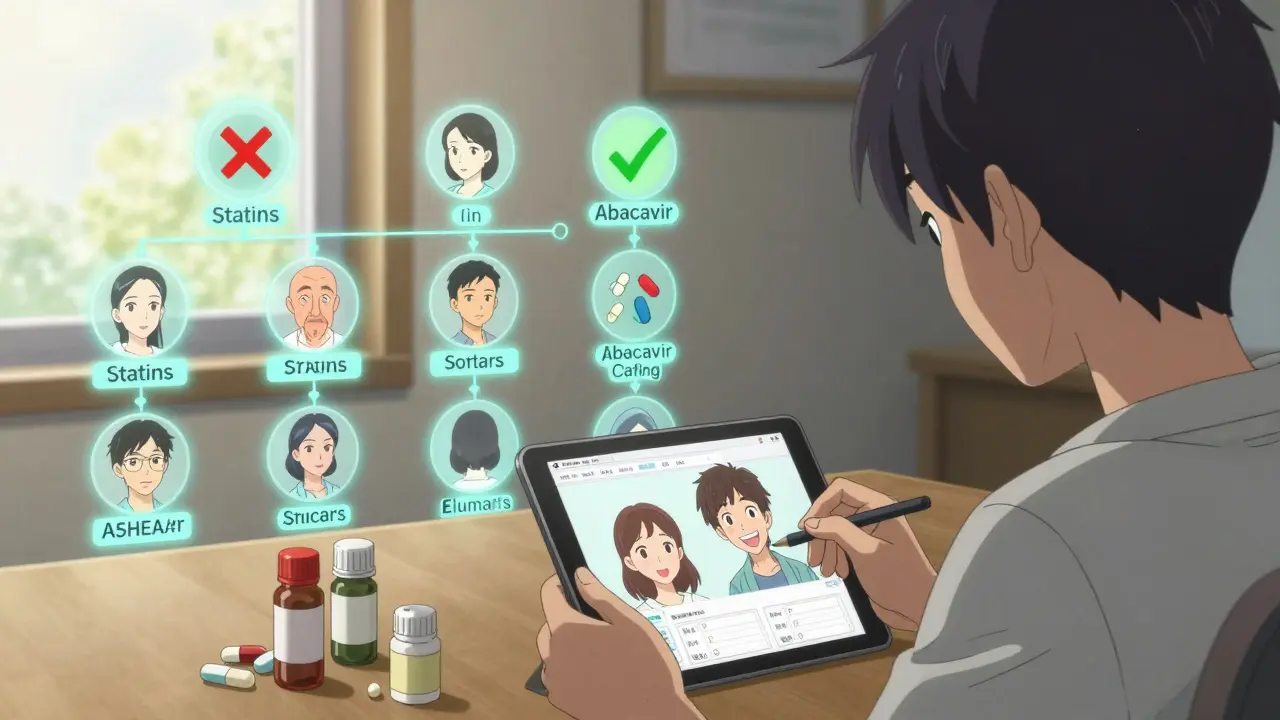

This isn’t theoretical. There are clear, life-saving examples. Before 2008, about 5% of HIV patients who took abacavir developed a deadly allergic reaction called hypersensitivity syndrome. Then doctors started testing for the HLA-B*57:01 gene. If you had it, you didn’t get the drug. The reaction dropped to almost zero. That’s 100% prevention for a condition that used to kill people. In cancer treatment, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a common chemotherapy drug. But if you have a DPYD gene mutation, your body can’t break it down. The result? Severe toxicity-diarrhea, mouth sores, even death. Testing for DPYD before starting treatment lets doctors lower the dose or pick a different drug. One patient in a MedlinePlus case study survived her cancer because her test flagged the risk before the first dose. For statins, the cholesterol-lowering pills, a variant in the SLCO1B1 gene increases the risk of muscle pain and damage by 4.5 times. If you’ve had muscle pain before and didn’t know why, testing could explain it-and help you switch to a safer statin or adjust the dose.What the Numbers Say About Effectiveness

A 2022 study in JAMA followed people with major depression who got genetic testing before starting antidepressants. Compared to those who didn’t, they had 30% fewer prescriptions with dangerous drug-gene interactions. That’s huge. But here’s the catch: after 24 weeks, there was no big difference in how well their depression improved. The test helped avoid bad reactions, but it didn’t magically fix their mood. Another study found that patients who had side effects from statins and then got tested were 60% more likely to stick with their medication three months later. Without testing, only 33% kept taking it. That’s not just about safety-it’s about getting the long-term benefit of the drug. The problem? Not every drug has a reliable genetic link. For tamoxifen, used in breast cancer, CYP2D6 status doesn’t consistently predict how well the drug works. The science is still catching up. Right now, pharmacogenetic testing only applies to about 300 of the 1,500+ drugs commonly prescribed in the U.S.

Who Should Consider It?

You don’t need to get tested just because you can. But here are situations where it makes sense:- You’ve had a bad reaction to a medication-even if it was mild.

- You’re starting a drug with a narrow safety window, like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antidepressants.

- You’re on multiple medications and your doctor suspects interactions.

- You have a family history of unexpected drug reactions.

- You’re being treated for cancer, heart disease, or mental health conditions where drug choice matters a lot.

What the Test Actually Involves

Getting tested is simple. You spit into a tube or get a cheek swab. No needles, no fasting, no special prep. The sample goes to a lab. In 3 to 14 days, you get a report that says whether you’re a poor, intermediate, normal, rapid, or ultrarapid metabolizer for key enzymes. But here’s the catch: the report alone isn’t enough. A result saying “CYP2D6 poor metabolizer” means nothing unless your doctor knows what to do with it. That’s why most successful programs tie the test directly into electronic health records. When a doctor prescribes a drug, the system flags if your genes suggest a problem. Most primary care doctors aren’t trained to read these reports. A 2021 study found only 35% felt “very comfortable” using the results. That’s why testing is more common in oncology, cardiology, and psychiatry-specialists who deal with high-risk drugs daily.Cost and Insurance Coverage

Out-of-pocket, a full pharmacogenetic panel costs between $250 and $500. That’s a lot if you’re paying yourself. But some insurance plans cover it-especially if you’re on a drug with a known genetic risk. Medicare and most private insurers will cover HLA-B*57:01 testing before abacavir. They’ll often cover CYP2C19 testing for clopidogrel in heart patients. But for antidepressants? Rarely. Only 22% of U.S. Medicare contractors cover pharmacogenetic testing broadly. Some companies offer direct-to-consumer tests, but many aren’t validated for clinical use. The FDA doesn’t regulate lab-developed tests the same way it does drug kits. That means quality varies. Stick to tests ordered through your doctor or a reputable pharmacy like Avant or GeneSight.

The Real Limitations

Genetic testing won’t give you a crystal ball. It tells you about one piece of the puzzle-how your body breaks down drugs. But other things matter too: your age, liver function, other meds you’re taking, even your diet. Also, about 15-20% of test results show variants of uncertain significance. That means scientists don’t yet know if the gene change matters or not. It’s a gray zone. Your doctor can’t make a clear decision, and you’re left wondering. And here’s something people don’t talk about: some people with high-risk genes never have side effects. Others without those genes do. Genetics isn’t destiny. It’s a guide.What Experts Really Think

Dr. Julie Johnson, a leading pharmacogenomics expert, says the test is most valuable for drugs where a small mistake can cause big harm. That’s why it works so well for warfarin, clopidogrel, and cancer drugs. For less critical medications, the benefit isn’t clear. The American Academy of Family Physicians warns that many commercial tests overpromise. Not all claims are backed by solid science. Some companies sell tests that include dozens of genes but only a few have proven clinical value. The FDA tracks over 300 drug-gene pairs in its official labeling. That’s your benchmark. If a test claims to predict your response to a drug not on that list, be skeptical.Should You Get Tested?

If you’ve been burned by medication side effects, or you’re about to start a high-risk drug, yes-get tested. It’s not a luxury. It’s a tool to avoid harm. If you’re healthy, on one stable medication, and never had a problem? Probably not worth it yet. The science is still growing. Costs are still high. Insurance coverage is spotty. The best time to test is before you start a new drug, not after you’ve had a bad reaction. But even if you’ve already suffered, testing can help you avoid repeating the same mistake. The field is moving fast. By 2024, Epic’s electronic health record system will include built-in pharmacogenetic alerts. More hospitals are adopting it. The cost will drop. Coverage will expand. Right now, it’s not for everyone. But for the right person-someone who’s been through the medication roulette game-it’s one of the smartest health decisions they can make.Is genetic testing for drug metabolism the same as ancestry DNA tests?

No. Ancestry tests look at markers tied to heritage and traits like eye color. Pharmacogenetic testing focuses only on genes that affect how your body processes medications. The lab, the analysis, and the purpose are completely different.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Yes, some companies sell direct-to-consumer panels. But without a doctor to interpret the results, you risk misunderstanding them. Some results need clinical context-like your current meds or liver health. A test without guidance can do more harm than good.

Will my insurance cover this test?

It depends. Insurance is more likely to cover testing for drugs with strong evidence, like abacavir, clopidogrel, or warfarin. For antidepressants or statins, coverage is rare unless you’ve already had a reaction. Always check with your insurer before testing.

How long do the results last?

Forever. Your genes don’t change. Once you have your results, you can use them for every prescription you get in the future. Keep a copy and share it with any new doctor.

Can genetic testing tell me which drug I should take?

Not exactly. It tells you how your body will likely respond to certain drugs, helping your doctor eliminate options that could cause harm or not work. The final choice still depends on your condition, other health factors, and your doctor’s judgment.

Are there risks to getting tested?

The physical risk is zero-it’s just a swab or saliva sample. But emotionally, results can cause anxiety, especially if you get a variant of uncertain significance. Also, there’s a small chance of genetic discrimination, though GINA law protects against health insurance and employment discrimination based on genetic data in the U.S.

What if my test says I’m a poor metabolizer but I’ve taken the drug before with no problems?

That’s not uncommon. Genetics isn’t the whole story. Other factors like liver health, age, diet, or other medications can affect how a drug works. Your doctor will consider your history along with your genes. You might still be able to take the drug, just at a lower dose.

Can I use my test results for my family members?

No. Each person’s genes are unique. Even siblings share only about half their DNA. Your results don’t apply to your parents, children, or siblings. They’d need their own test.

9 Responses

Genetic testing for drug metabolism is a brilliant idea in theory, but let’s be real-most doctors don’t know how to interpret the results, and insurance won’t cover it unless you’re already in the ER because of a bad reaction. So we’re paying $500 to confirm what we already know: that some drugs make us sick. It’s a luxury diagnostic for people who can afford to be guinea pigs.

One must question the underlying assumption that genetic determinism in pharmacokinetics is anything more than a statistically significant correlation masquerading as clinical certainty. The notion that a single nucleotide polymorphism can dictate therapeutic efficacy, without accounting for epigenetic modulation, microbiome variability, or environmental cofactors, is not merely reductionist-it is scientistic hubris dressed in the lab coat of precision medicine. One cannot reduce the human organism to a biochemical algorithm, and to suggest otherwise is to ignore the fundamental complexity of biological systems.

Did you mention that 15-20% of results are variants of uncertain significance? That’s the real problem. People see ‘CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizer’ and panic. They stop their meds. They Google. They convince themselves they’re going to die. Meanwhile, their doctor has no idea what to do. This isn’t empowerment-it’s anxiety sold as innovation. And the companies know it. They’re not selling science. They’re selling fear.

My dad took warfarin for years and never had a clot. Then he got tested-turns out he’s a slow metabolizer. Dose cut in half. No more bruising. Best $300 he ever spent.

So if I’m a fast metabolizer and antidepressants don’t work for me, does that mean I’m just genetically broken? Or is my brain just too damn strong for pills? I’ve been on 7 different SSRIs. None worked. I didn’t get tested. I just stopped taking crap that made me numb. Maybe the real problem isn’t my genes-it’s the fact that we treat depression like a broken pipe.

As someone from India, I’ve witnessed firsthand how pharmacogenomics remains inaccessible to the majority. While Western clinics offer GeneSight panels, in rural hospitals, patients are prescribed statins and antidepressants without any genetic insight-simply because the infrastructure doesn’t exist. This isn’t just a scientific gap; it’s a global equity crisis. We celebrate precision medicine in Silicon Valley while millions die from avoidable adverse reactions due to lack of basic diagnostics. The technology is here-but the justice isn’t.

India has over 1.4 billion people and maybe 3 labs that do this testing properly. But I’m glad someone finally wrote this. My cousin took clopidogrel after stent placement and had a heart attack. Turned out she was a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer. No one tested her. She’s fine now, but barely. This isn’t sci-fi-it’s survival. 🙏

The philosophical underpinning of pharmacogenetic testing reveals a profound tension between individual autonomy and systemic inefficiency. While the individual benefits from personalized therapeutic strategies, the broader healthcare infrastructure remains ill-equipped to integrate such data meaningfully. The disconnect between technological possibility and institutional readiness reflects not merely a logistical challenge, but a deeper epistemological failure: we have the knowledge, but lack the wisdom to implement it equitably. Until medical education evolves to include pharmacogenomics as a core competency, such tests will remain privileged artifacts rather than public health tools.

Look, I got tested after my third antidepressant gave me tremors. Turned out I’m a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer. Took me 2 years and three hospital visits to figure out why nothing worked. Now I’m on a different med. No side effects. Life’s better. But here’s the thing-my doctor didn’t even know what CYP2D6 meant. I had to print out the FDA table and show him. So yeah, the test works. But the system? Still broken.